by Ashraf F. Fouad, D.D.S., M.S..

Antibiotics frequently are used by dentists and endodontists as part of routine practice in endodontic therapy. In addition, some endodontic patients are at risk of developing bacterial endocarditis or prosthetic joint infections, and several guidelines have been proposed to prevent these infections during endodontic treatment. The AAE produced several previous position statements and guidelines on the use of antibiotics in conjunction with endodontic treatment. However, these guidelines need to be examined periodically to determine their currency and validity.

Antibiotics frequently are used by dentists and endodontists as part of routine practice in endodontic therapy. In addition, some endodontic patients are at risk of developing bacterial endocarditis or prosthetic joint infections, and several guidelines have been proposed to prevent these infections during endodontic treatment. The AAE produced several previous position statements and guidelines on the use of antibiotics in conjunction with endodontic treatment. However, these guidelines need to be examined periodically to determine their currency and validity.

In this regard, Dr. Linda G. Levin, past president of the AAE, assembled a special committee to examine current usage of antibiotics in endodontics. Specifically, the committee was charged to: 1) develop guidelines for prescribing antibiotics, and 2) review the previous AAE Quick Reference Guide. The committee was to examine the literature, trends and existing guidelines relative to the use of antibiotics in endodontics and provide an update that could guide the specialists on the state of knowledge in this area. This effort was both necessary and timely, given concerns about the overuse of antibiotics in dental practice, and the recent controversies in the guidelines for the antibiotic prophylaxis of patients at risk of serious systemic infections.

After an effort that lasted a few months, the committee generated its findings in the form of a narrative review that was submitted to, and eventually approved by, the AAE Board of Directors. The document examines available literature in areas related to the risks and benefits of antibiotic prescription and the evidence supporting the use of antibiotics to supplement treatment, in cases in which adequate local debridement has been achieved. The review also discusses whether there is value in prescribing antibiotics in cases where local debridement could not be achieved, the indications for culture and sensitivity testing, and the comparative analysis of the available antibiotics. The distinction between localized and spreading infections is defined, as it is very relevant to the indications for antibiotic prescriptions. The role of prophylactic antibiotics prior to endodontic surgery, and whether they affect long-term healing also is addressed.

Finally, the document presents the currently accepted guidelines for antibiotic prophylaxis in cases at risk of bacterial endocarditis and prosthetic joint infection, and recent discussions and debates in this area. These guidelines were excerpted from other dental sources where they were published, with emphasis on special situations and circumstances that commonly arise in practice. There was also additional elaboration on examples of patients who may need special attention with respect to antibiotic prophylaxis, when the guidelines indicated that no coverage was necessary.

The new guidelines are currently available online at www.aae.org/guidelines. They include AAE Guidance on the Use of Systemic Antibiotics in Endodontics, AAE Guidance on Antibiotic Prophylaxis for Patients at Risk of Systemic Disease and an update to the AAE’s Quick Reference Guide on Antibiotic Prophylaxis. The AAE’s Guidance on the Use of Systemic Antibiotics in Endodontics will be published in the Journal of Endodontics in September.

|

AAE clinical guidelines and position statements to aid all dentists in evaluating patients and performing quality endodontic treatment.

|

||

Dr. Ashraf F. Fouad is the chair of the Department of Endodontics at the University of North Carolina School of Dentistry. He earned his master’s degree, certificate of endodontics and D.D.S. from the University of Iowa. Dr. Fouad is a Diplomate and past president of the American Board of Endodontics and an associate editor of the Journal of Endodontics. He served as chair of the AAE Special Committee on Antibiotic Use in Endodontics. Dr. Fouad can be reached at [email protected].

Cone Beam CT Interpretation: With Great Power Comes Great Responsibility

By Bruno Azevedo, D.D.S., M.S.

Cone beam computed tomography has become an important tool in the diagnostic imaging spectrum of endodontics and is one of the most discussed topics within the endodontic specialty today. Almost all endodontists graduating from residency programs in North America have direct access to CBCT imaging, with a significant number of practicing endodontic specialists either owning or having access to 3-D imaging. This is no wonder as most CBCT users state, “I can see so much more with my cone beam.”

The AAE, together with the American Academy of Oral and Maxillofacial Radiology, has provided evidence-based guidelines regarding the applications of this imaging modality in endodontics. Small field of view, high-resolution volumes of the oral and maxillofacial complex provide superior diagnostic capabilities compared with conventional 2-D imaging in several clinical situations. These include the display of key anatomic structures and their relationship to the dentition, visualization of tooth morphology without superimposition, evaluation of tooth and bony pathosis, surgical planning and endodontic therapy outcome evaluation. CBCT has undoubtedly provided us with great imaging power. With this power comes a great responsibility to interpret 3-D volumes.

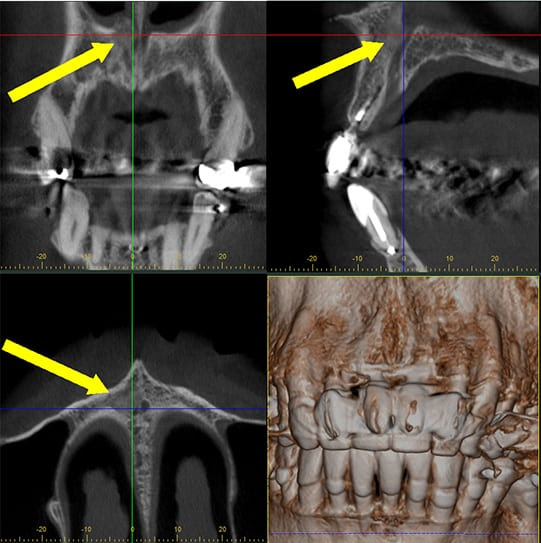

CBCT scan acquired to evaluate tooth no. 24 demonstrates a non-homogeneous high-density finding in the incisive canal area eroding the floor of the right nasal fossa. Biopsy of the area revealed this finding to be metastasis from prostate cancer.

There is no controversy in dental practice regarding the responsibility of dental practitioners in interpreting all radiographic findings on 2-D radiographs in the dental practice. However, for an endodontist who acquires a CBCT scan, some have questioned who is responsible for the interpretation and legal responsibilities regarding incidental findings. The answer is simple. Just like for 2-D imaging, a clinician who acquires or interacts with the CBCT volume (even if acquired in another practice or imaging center) is responsible for the interpretation of the acquired or provided volume. Some colleagues are under the misperception that they are only responsible for the endodontic interpretation of the volume. The responsibility for radiology interpretation is not technology dependent. Clinicians are responsible for all information within the 2-D radiograph and/or CBCT volume, regardless of the intent of the exam. Oral and maxillofacial radiology is a recognized specialty in dentistry. Practitioners who perform and evaluate CBCT scans are held to the same professional standards as Board-certified radiologists. As CBCT imaging becomes more popular, learning how to interact with the data to recognize incidental findings, that is, unrelated findings to the original intent of the scan, becomes imperative. Incidental findings are more identifiable in 3-D imaging than in 2-D radiographs.

The need to identify incidental findings in CBCT volumes should not be based on the fear of liability and malpractice. It is in the best interest of the patient as well as the provider to recognize incidental findings as many have the potential to change a treatment plan. Developing a systematic and reproducible method to review volumes can improve productivity and minimize interpretation time. CBCT interpretation consists of three phases: image acquisition, data interaction and description of all radiographic findings. Clinicians should avoid interpreting low-quality scans if a retake is possible. Proper documentation of the presence of CBCT artifacts, such as beam hardening and streaking, is highly encouraged, as they may compromise interpretation of the scan. Some endodontists use the CBCT scan as a tool, such as a microscope, and provide no documentation of its use during endodontic therapy. It is imperative that endodontists report all their interpretation findings (both primary and incidental) in the patient’s chart. This is only the first stage of radiographic interpretation, which is to recognize normal versus abnormal anatomy and pathology. Secondly, differential diagnosis for such incidental findings should also be provided. If help is needed to provide interpretation of CBCT scans or to come up with differential diagnosis for incidental findings, a consultation with a Board-certified radiologist is highly encouraged because they are trained to read and provided expert consultation.

Another important issue to combat the fear of liability regarding CBCT scans is education. Unfortunately, most endodontists and endodontic residents receive little to no training in CBCT interpretation. Access to this imaging technology does not translate into clinical proficiency. Many authors have demonstrated that numerous incidental findings occur outside of the area of interest and stress the importance of learning how to systematically review a CBCT scan and report imaging findings. A recent study comparing the detection of incidental findings in CBCT scans acquired for endodontic purposes demonstrated that oral and maxillofacial radiologists may observe 50 percent more incidental findings than clinicians. Endodontists who use CBCT should seek continuing education in CBCT interpretation to broaden their knowledge spectrum in radiographic diagnosis. Regardless of the CBCT scanner, “your eyes can only see what your brain knows.” Knowledge is power.

Dr. Azevedo is a Board-certified oral and maxillofacial radiologist and assistant professor in the Department of Hospital and Surgical Dentistry at the University of Louisville School of Dentistry. Dr. Azevedo can be reached at bruno.deazevedo@louisville.

Works Cited

- Setzer FC, Hinckley N, Kohli MR, Karabucak B. A survey of cone-beam computed tomographic use among endodontic practitioners in the United States. J Endod 2017;43:699-704.

- AAE and AAOMR Joint Position Statement: Use of Cone Beam Computed Tomography in Endodontics 2015 Update. Special Committee to Revise the Joint AAE/AAOMR Position Statement on Use of CBCT in Endodontics. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol 2015;120:508-12.

- Schloss T, Sonntag D, Kohli MR, Setzer FC. A comparison of 2- and 3-dimensional healing assessment after endodontic surgery using cone-beam computed tomographic volumes or periapical radiographs. J Endod 2017;43:1072-9.

- Carter L, Farman AG, Geist J, Scarfe WC, Angelopoulos C, Nair MK, Hildebolt CF, Tyndall D, Shrout M. American Academy of Oral and Maxillofacial Radiology executive opinion statement on performing and interpreting diagnostic cone beam computed tomography. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod 2008;106:561-2.

- Friedland B, Miles DA. Liabilities and risks of using cone beam computed tomography. Dent Clin North Am 2014;58:671-85.

- Scarfe WC, Li Z, Aboelmaaty W, Scott SA, Farman AG. Maxillofacial cone beam computed tomography: essence, elements and steps to interpretation. Aust Dent J 2012;57 Suppl 1:46-60.

- Oser DG, Henson BR, Shiang EY, Finkelman MD, Amato RB. Incidental Findings in Small Field of View Cone-beam Computed Tomography Scans. J Endod 2017;43:901-4.

- Edwards R, Altalibi M, Flores-Mir C. The frequency and nature of incidental findings in cone-beam computed tomographic scans of the head and neck region: a systematic review. J Am Dental Assoc 2013;144(2):161-70.